A new batch of solar images captured by the Solar Orbiter has revealed groundbreaking views of our star’s visible surface with unprecedented resolution, showcasing sunspots and swirling streams of charged particles (plasma). These images may provide new clues for solar physicists to unlock the secrets of the sun.

According to CNN, the images were taken on March 22, 2023, and released on Wednesday (November 20), displaying various dynamic features of the sun, including the movement of magnetic fields and the corona’s (outer atmospheric layer) superheated halo.

The Solar Orbiter, a joint mission launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA in February 2020, along with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, is helping to answer key questions about this golden orb, such as where the charged particle flow known as solar wind originates from and why the corona’s temperature is much higher than the sun’s surface.

This spacecraft relies on two of its six imaging instruments, namely the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) and the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI), to capture these images from a distance of 46 million miles (74 million kilometers).

The PHI instrument aims to map the brightness of the sun’s visible surface (photosphere) and measure the speed and direction of the solar magnetic field. Meanwhile, the EUI observes the solar corona to help determine why its temperature is significantly higher than the photosphere, reaching 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (1 million degrees Celsius).

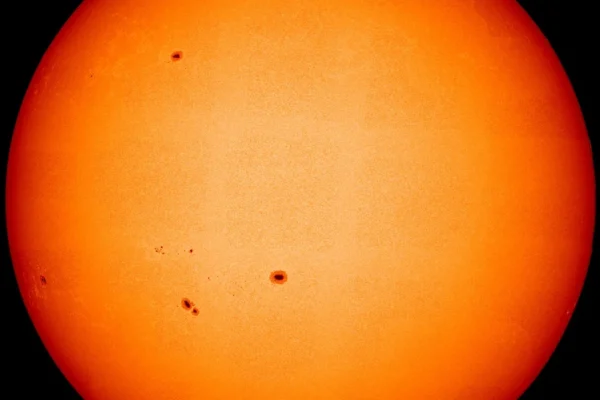

The PHI has captured the highest resolution panoramic view of the sun’s visible surface (photosphere) to date. Almost all radiation from the sun originates from the photosphere, with temperatures ranging between 8,132 to 10,832 degrees Fahrenheit (4,500 to 6,000 degrees Celsius). Below the photosphere, hot plasma continuously churns in the sun’s convection zone.

Mark Miesch, a research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center, stated, “To understand the relationship between the twisted magnetic fields and the swirling plasma flows, we need a comprehensive view of the sun. These high-resolution images from the Solar Orbiter bring us closer to this vision than ever before.”

Miesch, also a research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado, not directly involved in this study, added, “The more closely we observe, the more we see.”

The visible light images of the photosphere display areas where the sun’s magnetic field pierces the surface – sunspots. These dark regions, some the size of Earth or even larger, are driven by the sun’s powerful and ever-changing magnetic fields, with temperatures lower than the surrounding environment and emitting less light.

Moreover, the Solar Orbiter is studying the sun at an opportune time – during the current peak of the solar cycle.

Scientists from NOAA, NASA, and the International Sunspot Cycle Prediction Group announced in October that the sun has reached the peak of activity within the 11-year cycle. During this time, the solar poles reverse, transitioning the sun from a calm state to an active one. Experts track the increasing solar activity by calculating the number of sunspots appearing on the sun’s surface. The sun is expected to remain active for the next year or so.

“This announcement doesn’t mean that we’ve reached the peak of solar activity in this cycle,” Elsayed Talaat, director of the NOAA’s Office of Space Weather Observation, stated during a news briefing in October. “Although the sun is at its maximum phase, pinpointing the specific peak months of solar activity may take several months or years.”

Solar activity, including flares and coronal mass ejections, can generate solar storms that impact Earth. Besides creating polar auroras, solar storms can affect power grids, GPS systems, aviation, and satellites in low Earth orbit, as well as causing radio interference and posing risks to manned space missions.

On December 24, the Parker Solar Probe will come within 3.86 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the sun’s surface, becoming the closest man-made object to the sun. This close encounter will help scientists study the origins of space weather directly at its source.